The Big Machine Theory

I made a decision — and a promise — to only talk here about things I had directly experienced.

And now I’m going to break that rule. Kind of?

I’ve been thinking a lot about the current state of creative endeavor, and what I call The Big Machine Theory. We’ve been in a relatively stable creative market since Gutenberg’s day. And then we had a revolution in mass communication starting in the nineties (hint: it begins with “http::”). And now we’re facing another revolution in the creative market, one that threatens to literally eat all creativity that came before it, and destabilize the ability of creatives to get paid for their work.

Let's talk about it after the news.

What’s going on?

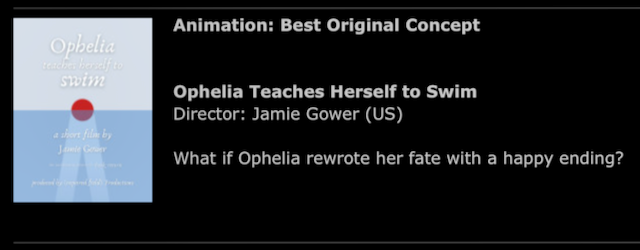

- Remember I mentioned I had a short film that was going to show at the Jane Austen International Film Festival in early September? Well, guess who won an award there?

- I did a short, fun interview for @paddygilmore.bsky.social’s most excellent Brands and Humor newsletter, in which I reveal the secret ingredient to humor that connects with people. (Hint: it’s not pumpkin spice, although that couldn’t hurt.)

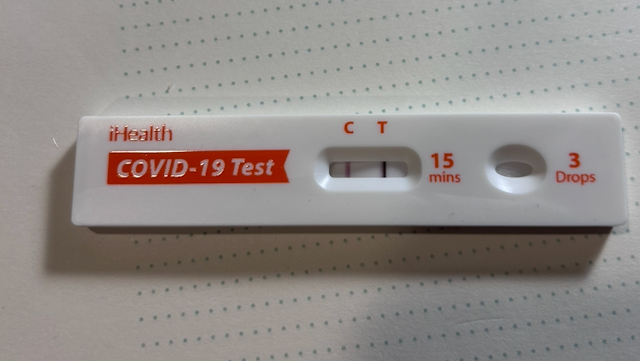

- And remember COVID? Looks like it’s still a thing, because I spent the last two weeks in its grip – including 2.5 days quarantined in a cruise ship stateroom. Such fun! Get your inoculations, folks. COVID well and truly sucks.

Enter the Big Machine

Used to be, if you wanted to talk to a lot of people — you know, mass communication — you needed a lot of people to produce your message and spread your message. And to get a lot of people together, you needed to have either an army or a religion. Those peasants building the pyramids? They were working for a military power. And those abbeys full of monks handwriting manuscripts in the Middle Ages, they were all working for a religion.

Then came the first Big Machine: the movable type printing press. This machine let you spread your message with just a few people. You don’t need an army, you don’t need a religion. You just needed that Big Machine. This shifted the ability – the power – of mass communication from religions and armies to anyone who possessed one of these Big Machines.

Big machines are big hungry babies

The one problem with owning a Big Machine was: now you owned a Big Machine. They’re expensive. Not only to buy, but also the entire time you own one. Every day. If you own a printing press, you have to feed it ink. You have to feed it paper. You have to have a special room just to house the thing. And while you don’t need an army, you are still going to need to pay employees to help you move all that paper and ink around.

So even when it’s doing nothing, the big machine is costing you money. So you need to continually use it to make stuff people will pay you for.

And this held true down the ages, whether you owned a printing press, a radio station, a TV network, or a streaming service. All of those are Big Machines. All require constant feeding whether they're working or not, so all these Big Machines need to constantly produce content.

The rise of the Gatekeepers

But you can’t just pump any content through your Big Machine. Because that content reflects back on the Big Machine itself. If you produce garbage, you will then own a Garbage Big Machine. Now, some people make good money making garbage, but it’s a limited, focused audience. Most Big Machine owners prefer a wider audience.

Founding Father Ben Franklin worked with and owned Big Machines (printing presses), and he invented alternate identities he wrote as to help fill his newspaper. This let him create content for and control the voice of his Big Machine. While this was cool in a Bruce Wayne kind of way, it wasn't really a scalable tactic. Luckily, he moved on to a new role as a Professional American in France before things got out of hand in the alternate identity department.

Owners of Big Machines had an existential interest in both attracting and selecting quality content to shove through their big machine. So they became the gatekeepers to their Big Machines – editors, producers, radio station execs, movie moguls. They became a small group that anyone creative had to target in order to get their stuff put into the Big Machines so it could be seen by the world.

It was a reverse funnel for creatives – get past a narrow gateway, and your work would be seen by a much wider crowd.

And, perhaps more importantly, if you were able to get your work approved by the gatekeepers to be produced by their Big Machine, you would get paid. And that money could then be traded for food and shelter. Thus the creator lives to create more.

The Internet busts open the gates – at a cost

Then came the Internet and digital media and smartphones. And almost overnight, all the capabilities of all the Big Machines were available to anyone with a smartphone and a broadband Internet connection.

Want to make a movie? Well, don’t worry about renting cameras or buying filmstock – just point your phone and press Record. Want to get international publication and distribution of your book? You can set that up by yourself in less than an hour.

The gatekeepers were suddenly gone, and anyone who wanted to could get their content seen worldwide. And that became the new problem.

Because the gatekeepers were suddenly gone.

Those gatekeepers had not only controlled what content was allowed into their Big Machines, they spent a lot of time and money attracting an audience to buy what came out of their Big Machines. So if you were a creator who made something that the gatekeepers wanted for their Big Machine, you suddenly had that whole organization working to make sure what you created was visible.

With the gatekeepers gone, suddenly everyone and everything was oddly the same. Creative work became tossing a message in a bottle into a worldwide ocean already filled with bottles – and with thousands, millions more tossed in every day on top of yours. Getting any individual work noticed suddenly became the creator’s problem.

And it became a lot harder to get paid.

Search engines, advertisements, and algorithms, oh my

To be fair, the gatekeepers aren’t exactly gone – there are still movie studios and TV channels, radio stations and magazines. And the internet made it easier for creators to find the gatekeepers and get their creations to them for Big Machine consideration.

But the internet has been steadily eating into how the gatekeepers do business, and how much business they do. And releasing on the web is an attractive option for creators that want more control of their work. So after spending literal centuries figuring out to talk to kings and popes, publishers and producers, now creators had to learn a whole new technology, and whole new language. They had to start talking to the internet itself.

The first tools that emerged to help people pull what they actually wanted out of the vast sea of everything were the search engines. Like Lycos, Webcrawler, Ask Jeeves, Alta Vista, Bing, DuckDuckGo, and yes, okay, fine, Google.

Since most people don’t even scroll down the first page of search results, much less look at page 2, suddenly where your page was ranked in search results became vitally important. Thus arose SEO: Search Engine Optimization, the science and dark art of making sure the structure, metadata, and even word choice of your web site was attractive to web searches (i.e., let’s face it, Google).

And once you were seen, how could you get paid? By ads, of course. This is, after all, late stage capitalism. Of course there are ads.

So now, creators on the internet had to figure out how to show advertisers that their sites were worth buying space on. TV had the Nielsen ratings, movies had box office sales. The internet was a little tougher to quantify. Creators had to gather data on how many people visited their site, how long they stayed, what buttons they pressed, what content they bought. The higher the numbers, the more lucrative the ad space.

And then came social media: Facebook, Twitter/X, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, Tumblr, etc. These were a new, inverted version of the Big Machine. Each had two major components: a close definition of what information format and length was allowed on their service, and their own algorithm to curate what content to show each user.

These algorithms became the new gatekeepers. Creators would not only make sure to fit the length and format allowed by the services, they would also customize their work itself to try to attract and/or not repulse the algorithm. Sneaking around the algorithm is why we have such conventions as saying “seggs” instead of “sex”, and using the peach emoji 🍑 instead of saying “butt.” (There’s more emojis used like this. So many emoji…)

AI – the Big Machine that eats Big Machines

And like any town established during a gold rush, the internet quickly filled with business, services, and apps to help creators with the work of SEO and ad sales. Online magazines, podcast networks, and newsletter services (!) sprang up to fill many of the same ecological niches of the previous Big Machines and gatekeepers.

Just like a gold rush town, it's crowded, noisy, confusing, and every once in a while somebody strikes it big.

Then came the Big Machine called Generative AI.

Generative AI can write, paint, even make movies. It does it by consuming immense amounts of content (called “training”), and then using what amounts to a very sophisticated autocomplete function to figure out which pixel should go next to which pixel based on all that content it consumed.

It’s pretty amazing. And it's raw, blatant theft. The big AI companies “trained” their models by copying everything they possibly could off the Internet – including copyrighted works they did not have the rights to. They knew this was wrong, but were hoping they would get too big to fail.

So not only do artists face the possibility of being replaced by Generative AI, it is using their own work to do so. It’s like someone stealing your car, and then using it run you down.

There has been a partial settlement with a group of authors, but it’s really only that: partial.

But that’s not the big disruption being caused by AI. And no, it's not the inordinate amounts of land, water, and electricity needed to keep these theft machines running. That’s disruption enough. On top of all that, AI is threatening the economic basis of all business on the internet.

Remember how SEO became the basis for artists getting seen and paid on the internet? If you were ranked high on a relevant search, more people would click over to your site.

Well, the last time you did a search online, you may have seen an “AI assisted” summary come up above the search results. Pretty handy, eh? You ask a question, and there’s the answer. No need to click on any other websites.

Except your click generates views for those websites, and those views generate ad revenue. Thanks to the AI summaries, now some websites are seeing their Google traffic going down by 50% or more. This is a problem for the very foundation of making money from creating any sort of content on the internet.

Look, it’s still early days for AI. I don’t think it’s going anywhere. Genies generally don’t go back in the bottle.

But AI is a Big Machine that subsumes all the Big Machines that came before it, and threatens the already uneasy relationship between Big Machine owners and the artists who feed their big, expensive babies.

Fun facts to know and share

Just finished watching The Sting—great movie. Released in 1973, set in 1939. I regret to inform you that the same time difference is a movie set in 1991. Good. Night!

— Chris Goodman (@cbgoodman.co) 2025-09-29T03:54:08.412Z

Appropriately frightening for Spooky Season.

Finally the game makes sense...

Got a favorite newsletter on Substack? This site has info and scripts you can use to encourage them to migrate to a non-Nazi supporting platform. (I'd like get a paid subscription to Austin Kleon and John Hodgman, but I can't bring myself to give money to a platform that supports and pays Nazis.)

Music is joy.

Over to you

I apologize if this issue is a bit of a downer. I’ve been thinking about Big Machines since way back when AI meant Alan Tudyk in I, Robot.

As an offering, allow me to present the following. It lives on my browser, behind a button marked “In case of bad vibes, press this."

Despite it all, I remain optimistic about the world, since there are people like you in it.

Until we talk again, I remain,

Your pal,

Jamie